|

The History of The "Old Alcohol Plant" |

|

|

Narrow beaches, with gentle to moderate slopes, are to be found at the southern tip of Port Townsend Bay. Here, native cultures thrived beside the protected waters. The same wisdom that guided them to choose the site for their ancient village, Tsetsibus, also saved them from being too confident in their power to battle the forces of nature. |

| Long before white man settled the area,

the Chimacum (a.k.a. Chemakuan or Tsemakum) people had a village

at the head of the bay. It is said to have been a gathering place

for nearly all of the tribes in the Puget Sound. From there, the

whole of Port Townsend Bay is visible . . . a perk that provided

them ample protection from a sea attack.

In 1891, a Swinomish elder, Old Patsy, held the last great potlatch this area has known. The protected canoe pond behind Skunk Island was filled with the canoes from the Quilleutes, Snohomish, Skokomish, Lummi, Suquamish and S'Klallam peoples coming to this great feast. A southwesternly-extending spit and the presence of Skunk Island help assure the waters, in which the Port Hadlock Marina now lies, remain relatively calm. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

From 1911 to 1913, the Classen Chemical Company made alcohol out of sawdust at a plant built at the southern tip of Port Townsend Bay. Its construction began in 1910, when the nearby town of Irondale was booming and its sister city, Port Hadlock, had not yet given up the fight, despite the Washington Mill Company's mill closure in 1907. |

|

|

|

|

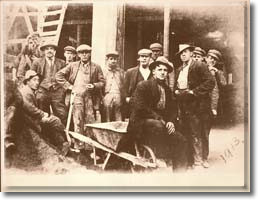

The Western Steel Mill, in Irondale, supplied the I-beams and rebar for the plant. The rebar was as thick as a man's wrist. Local laborers, from Chimacum, Port Hadlock and Irondale, poured tons of concrete and laid wagon-load upon wagon-load of locally-made bricks. The cost? More than $500,000. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

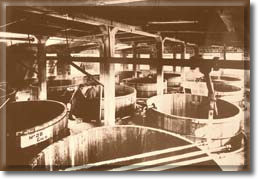

Classen made its alcohol using a French distilling process known as the Berigus Process. Wood waste, shredded into chips, was dried in a steam dryer until it contained no more than one percent moisture. The wood was mixed with cold 40 percent hydrochloric acid. The cellulose was converted to glucose, and the lignin extracted. |

|

|

|

|

Through evaporation, the acid was also recovered and reused. Fresh supplies of the acid were made in stone tanks from salt and sulfuric acid. Special yeast, grown in the plant, was added to the fermentation tank housing the glucose-rich wood solution. When the "beer" was ready, the eight-percent-alcohol solution was moved from the beer well and entered the distillation stage. This distillation |

|

|

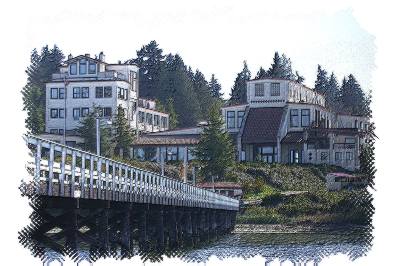

yielded "fusel oil," 190-proof ethyl alcohol. The neighboring cattle also benefited: the spent wort was used for feed. Local investors lost all they had put into the venture, when problems with the competition, bad management and rumors of mildewed product forced its demise. In 1978, Ray Hansen first laid eyes on the alcohol plant's dilapidated shell. The slimy remains of the by-then-ancient dock were visible at low tide. As the tribal elders and alcohol entrepreneurs before him, Hansen recognized the assets the site offered. Except at zero tide (and then only on its shallow side) the 38-foot deep marina had sufficient water to welcome the pleasure crafts that would frequent it. Nine years and $4 million after Hansen first laid eyes on the site, he and his wife Jeanne, finally had a hotel and resort they could be proud of. It was modern and luxurious, yet still reminiscent of the "Old Alcohol Plant.". In 2002, under new ownership, a total remodel of the resort marked the birth of the "Inn at Port Hadlock," a unique boutique hotel on the Olympic Peninsula.

|

|

|

|

|

inquiry(at)sandyhershelman.com

Copyright © 1991-2003 Sandy Hershelman. All rights reserved.